Frost protected foundations - essential in cold climates

Protecting homes and buildings in cold climates from structural damage caused by frost heave is essential for durability. In most parts of Canada and the northern United States, the ground freezes during the winter months to a depth of several feet. Such ground freezing can lead to heaving of buildings located above or adjacent to it and can even cause horizontal rather than just vertical movement.

When building a new home, properly insulating basements and engineering slab on grade foundations for homes not only prevents foundations from cracking, it also reduces energy consumption and global CO² emissions. The negative environmental aspects of concrete use can be mitigated by good engineering to use finite quantities based on structural need, and by using it proactively for thermal mass.

There is hardly any limit to the force that can be exerted by water when it freezes; even the weight of tall buildings cannot withstand the damage that can be caused when ice forms below them. A force of 19 tons per square foot has been measured with one seven-story reinforced concrete frame building on a raft foundation that heaved more than 2 inches. But, preventing frost heaving is actually a breeze as long as you design properly, and here we tell you how.

What causes frost heave and where?`

Ground frost heave, at its most simple, happens when ground water in cold climates changes from a liquid to a solid. Water expands by 9% when it freezes, so for any structure that is seated above the frost line – be it a deck, shed, slab on grade or a basement foundation, when expanding soils forces it upwards, it can go on a little ride if it was not properly engineered or protected from the elements. This leads to cracked foundations, shifting decks, and damage to basements and slab on grade homes.

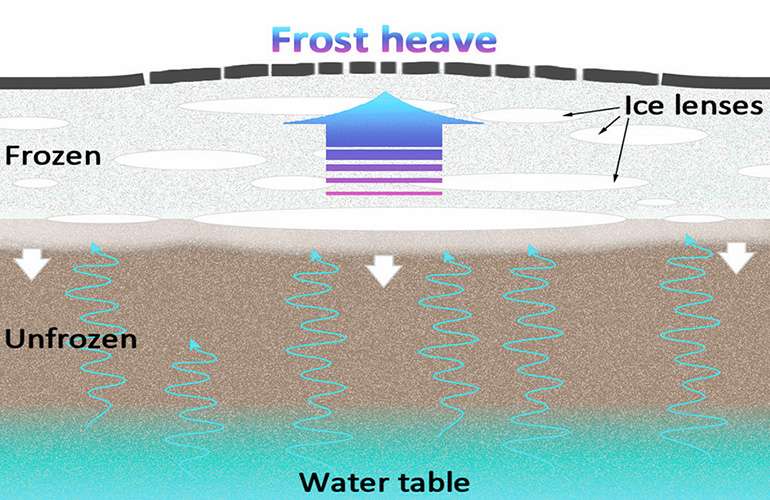

While the solutions to preventing frost heave are the same, the ‘actual’ cause of frost heave is somewhat misunderstood. It is mostly thought that the upward expansion of existing moisture in soil is what causes frost heave, but it’s slightly more complicated. So, for building nerds who want the real skinny on what’s going on, it’s a bit like this -

There is latent heat in the ground from summer months, so when winter arrives, ground freezing it is a progressive effect that happens as the temperature drops over many months. The freeze begins to move downward as air temperatures begin to stay consistently below zero, but there is always soft and warmer soil below.

The build-up of ice happens largely because water in the unfrozen soil below gets drawn up into the freezing zone and attaches itself to the existing frost crystals to form ever thickening layers of ice. The key phrase for this phenomenon is "ice segregation". This is what causes the expansion that forces soil particles apart, and is what causes the ground to heave upwards. But did you really need to know that? Yep. And you can thank me in the comments section after you pull out that little nugget at a dinner party and impress your friends.

What problems can frost heaving cause?

The pressure of frost heaving can crack basement walls - especially when built of CMU or brick - or with the lifting forces of frost heave caused by "adfreezing," which occurs when soil freezes to the surface of a foundation.

The heaving pressures developing at the base of the freezing zone are transmitted through the adfreezing bond to the foundation, producing uplifting and separating forces capable of pulling CMU apart by vertical displacement of a horizontal mortar joint near the depth of frost penetration. This is very important to consider when insulating a basement or insulating a crawlspace in an older home from the inside.

The forces involved in frost heaving can also be very destructive to lightly-loaded structures and cause serious problems in major ones - so when there are both within the same overall home structure (like a deck attached to a house with a basement), the differential movement can literally rip elements of a home apart.

Another aspect of frost heaving we have seen, especially in clay soils, that's highly inconvenient if not as destructive as a deck separating from a house, is where fence posts move around over winter and then never quite settle back - leaving the fence in a sorry state by the spring.

Frost heave prevention when building a home

Preventing frost heave is not difficult; you simply need to add sufficient insulation for your climate to prevent frost from getting underneath the base of your structure. Sufficient drainage is also important to keep water away from what you're building, this is also important for basement durability to reduce the chances of damage caused by flooding or high levels of humidity.

First, we should dispel any myths – you don’t ‘need’ to put dirt against a home to prevent frost heave. A slab on grade is not at greater risk from frost heave than a basement if it is built properly - in which case the correct term is a Frost Protected Shallow Foundation - or FPSF.

So if a general contractor tells you that you 'must' have a basement, they are simply wrong. That’s often someone who doesn’t know how to build a FPSF slab but still wants your money, so they may try to fill your head with their own misconceptions to get the job.

In most cold climates we have grown accustomed to having basements, and adopted the notion that a house needs to be in the ground to be below the frost line. That just isn’t so. You also do not need to pile dirt against the side of your house to stop it from tipping over. It’s just that dirt has always been used as insulation against frost heave, so it has been ingrained in us for centuries as essential. But, thanks to modern building practices, you can also use ‘insulation’ as insulation against frost heave!

Soil has an insulating value of about R3 per foot, where foam insulation will be between R3 and R5 per inch. That’s why you can build in an area where the frost depth is 4 feet in winter by using 4 inches of insulation instead of 4 ft of dirt. As a quick caveat – there are many types of rigid insulation but they aren’t all suitable for below ground; see here to find the right rigid foam insulation for foundations.

How much does frozen ground heave?

Terrain with high water tables and particularly expansive soils such as peat or clay often suffer from frost heave and damage buildings. It’s not uncommon to see a deck or shed move as much as 7 or 8 inches, and in some cases much more than that, even up to two feet. Buildings of 3 or 4 stories can easily be forced upwards by several inches. How severe the shifting can be depends on the soil type and its ability to contain moisture or bulk water, and of course the weight of the building or part of a structure to be lifted.

In very harsh winters, we've seen sidewalks and roadways heave up 6 inches or more, and separate blacktop vertically from curbing, which is embedded deeper and on a gravel base. Both the extra drainage and the deeper depth were keeping the water away from under curbing that was obviously present and freezing under the porous blacktop.

Does gravel prevent frost heave?

Yes, a good drainage base will help prevent frost heave. Gravel or crushed stone does not hold moisture, so it makes an excellent base. Sand works as well; it takes a layer of about 4 to 6 inches to be safe.

As mentioned above, a slab on grade is not at any greater risk of frost heave than a basement, full stop. Read more here – Choosing between a slab on grade and a basement. You can build a basement right or wrong, you can build a slab right or wrong. Just do it right and you will have no problem.

And if you happen to have bought some swamp land in a cold climate somewhere while you were drunk in a bar, don’t give up hope; see here for how to build Frost Protected Shallow Foundations on problem soils like clay soils that are susceptible to frost heave. Maybe you made a smart purchase after all. : )

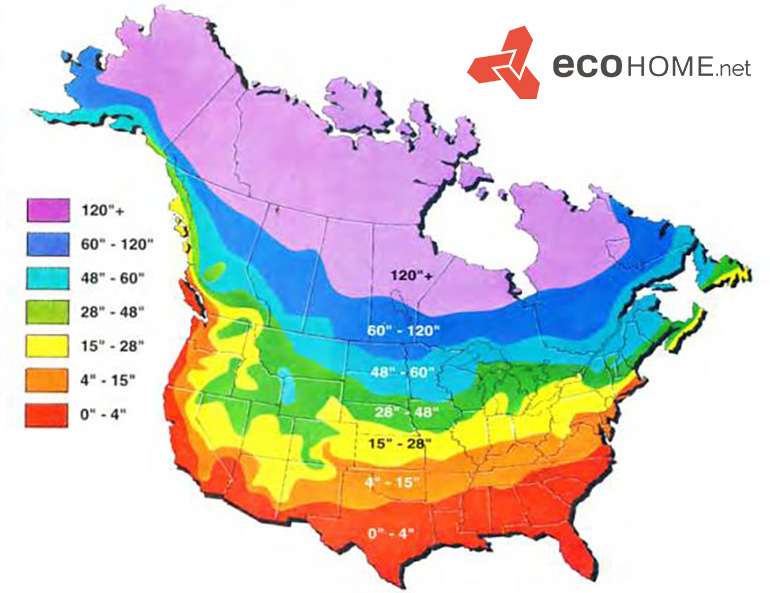

There are general rules for given areas on how deep the frost line is, ranging from a few inches in the Southern States to as much as 6 or 7 feet in the far north. Find out what building climate zone you are in, and be sure to check with local-municipality building inspectors to know for sure how deep you might need to go to get under the frost line.

This is, of course, great as a general rule if you are building something without permits or building inspectors, but for anything of greater consequence like full home construction, don’t chance it in the least. Buildings should be engineered properly for their specific climate.

Will frost heave go away?

Generally yes, if you have a smaller building or structure that has experienced frost heave, it will often settle back down close to its original position. But as quick as it drops in spring, it will lurch back up in the winter if you don’t deal with it.

Frost heave usually starts to happen in January or February as the cold penetrates the ground, and come spring, when it thaws, it will usually drop back close to its original position. ‘Close’ to it, but not always. This may be okay for little out buildings like wood sheds, and they may not suffer much damage. It’s the bigger things like houses that will see permanent damage. The other problem is where any of the services like water pipes, sewage, natural gas pipes or electrical connections are made underground.

Recap: the essentials to prevent frost heave

To prevent or fix frost heave, you have to either deal with the water in the ground, or the temperature of the ground, and ideally both. You need to make sure water drains away from the problem area, not towards it. Start your forensics and solution-hunting first with the roof’s storm water runoff, and direct it someplace where it does no harm. That can be with eavestroughs or gutters directing water towards swales, dry wells, or rainwater collection barrels.

There is also the option of directing water towards the street, and that’s better than towards your house. But on a grand scale, directing water to hard surface municipal water runoff has negative ecological consequences of its own. Best is to learn how to manage stormwater runoff and actually use that water to your advantage; read more here.

Once you have limited the potential damaging input of any water coming off your roof, you need to grade your landscaping properly to direct rainfall intentionally. Even a 2% slope away from homes, decks, sheds or whatever, is all it takes to move water in a safer direction. If it’s particularly expansive soil like clay, digging up the top few inches and laying down a waterproof membrane of some kind is an extra measure that can help keep soil dry, but be careful - as drying out expansive clay can also cause subsidance and cracking on older home foundations.

Skirt insulation works as well, which involves laying down a sheet of rigid EPS foam insulation (sloped away from the building) for preventing soil wetting, but more importantly that is how to move the frost line. So the real takewaway here, is that water and cold breaks things but insulation and water diversion saves things. As long as you remember that and design accordingly, there’s never a reason to worry about frost heave.

![]()

Now you know more about how to protect foundations and slabs from frost heave. Learn more about best practices for energy efficient and durable basement construction and renovations in these pages:

Find more about green home construction in the Ecohome Green Building Guide pages - also, learn more about the benefits of a free Ecohome Network Membership here. |

Comments (0)

Sign Up to Comment