What is Passive House certification?

The term “Passive House” was once obscure jargon used solely by construction engineers & technically-minded home designers, but now "certified Passive House" is being increasingly specified by construction professionals and homeowners across North America. The concept of Passive Solar heating for homes is gaining ground here as in the rest of the world - After all, who wouldn’t want a more efficient house - one that could radically reduce home energy bills by being built efficiently enough to create huge energy savings compared to a standard "code built" house? Especially if it is possible to build comfortable and super-efficient homes to Passive House standard at around the same cost of those currently being built (and which use a tenth of the energy - which it is... read on!)

Passive House Certification - PHI v PHIUS

Building to Passive House certified standards is, without a doubt, a potentially serious technical challenge for most average house builders in North America. To further complicate matters is the fact there are not one but two certification bodies in the US, PHI (Passive House Institute) and PHIUS (Passive House Institute US) and for Canada there is Passive House Canada and the Canadian Passive House Institute. This guide aims to describe the origins of Passive House certification, which can be accredited to a very futuristic Passive Solar heating design home built in the 1970's in Saskatchewan by a team led by Harold Orr, designer of the first modern Passive House that worked, who recently won the Order of Canada for his achievements with Passive Solar design, air-tightness for homes and energy-efficient houses. We at EcoHome salute you Mr Orr, thank you!

Where & when did "Passive House" start?

The Conservation House in Saskatchewan was built in 1977, and was a revolutionary building design that introduced passive solar heating and cooling to modern Passive House home building. Because let's get one thing straight - Passive Solar heating and cooling as a concept has been around for thousands of years. When early man was cold and it was sunny out he sat in the sun, when he was cold and it was overcast he sought shelter and lit a fire, unless of course it was sunny and he was too hot - and then he sought shelter too!

The difference with the extraordinary and pioneering Conservation House in Northwest Regina was it was one of the first buildings in the world to combine airtightness, super insulation for homes and a heat recovery ventilation system in an attempt to produce Zero Energy homes by design.

Harold Orr has won many awards for his work, but he said he wasn't expecting the Order of Canada; "It almost floored me, I wasn't expecting this at all."

We love that Orr said he was inspired to do his work in energy efficient home design through growing up on the prairies of Canada in the 1930s. As he puts it; "When I was going to school in public school somebody had to get up in the middle of the night to put coal on the fire otherwise we'd be cold in the morning." Just think, if they'd had high performance stoves and fireplaces "back in the day," Harold Orr might have spent his life doing other stuff rather than advancing building technology for the planet's benefit!

Later, at the University of Saskatchewan, he got more technical with his concerns, studying air leakage in homes, and then further research led to progressing the idea of passive solar design, which helps homes gain and retain natural heat from the sun through structural design and effective insulation choices (which is where traditional earthships fall down and don't work in cold climates according to our Mike Reynolds ).

Harold Orr wishes there were more passive solar energy homes in Saskatoon today, in fact throughout North America; "Everybody should be building the equivalent to the passive house," he said recently, and EcoHome agrees, though we do have "a thing" for non-toxic homes too, especially as high-efficiency homes tend to be more airtight, so the chemicals we choose to use in our homes and the materials we build them from are more important than ever. More of that here.

Passive House certification, when did that start?

Back in 1990, the father of the Passive House Institute (PHI), Dr. Wolfgang Feist, built the first “passive” house in Darmstadt, Germany using the latest building science to dramatically increase the building’s energy efficiency. PHI then put together a certification system based on those very high performance standards - guidelines to help others achieve the same results. Ten years later, at Dr. Feist’s urging, Katrin Klingenberg, a German architect, introduced these concepts (back) to the United States.

From the start, it was clear that some of the PHI methodology would need adapting to carve out a place for itself in the North American market. Just the simple process of converting all the measurements from metric to imperial in PHI’s Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) software boosted its popularity immensly in the USA & Canada.

Klingenberg and other members of PHIUS then launched a collaboration with energy sector leaders to adapt the PHI performance standards to North American climate realities (we’ll get back to that) to try to make the standard accessible to all. Across the pond, PHI was not at all keen to see these collaborations, even less to see their standards converted or deviated from and they officially cut the official support and connection in 2011.

So in North America there are two Passive House Certifications - PHI & PHIUS?

Since the "Divorce" between PHI & PHIUS, there are two certifications, yes, and the Debate among ecological passive house builders has been raging ever since 2011 about which certification constitutes the "right" way to build a passive house. It was a bit of a messy divorce - depending who you believe, PHI or PHIUS terminated the relationship first, but as the founder of the certification process (and without taking sides), here's Dr Feist's account of things... In a letter to press, Dr. Feist praised his "handpicked" US director Katrin Klingenberg for her work, but then stated “Unfortunately, recent actions by PHIUS have culminated both in breaches of contract and good faith, unnecessarily reinforcing false divisions within the Passive House community. In light of PHIUS’ disregard for its standing agreements with PHI, we are left with no other choice but to suspend all standing contracts. Evidence of PHIUS’ certification of Passive House buildings without the requisite documentation has threatened the integrity of the Standard and forced PHI to terminate PHIUS’ status as an accredited Passive House Building Certifier.”

He went on to describe three actions that PHIUS had made that did not go down well, and that in his words led to the termination of the PHI / PHIUS relationship. The US organisation was unauthorized to sell the primary design software Passivhaus Planning Package (or PHPP), and did not have permission to change the software often stated as converting it from metric to English measurement units (although again, opinions vary). Feist also stated that PHIUS had begun a “competing professional certification scheme” while not following their official Passivehaus contractual obligations. Finally, and most damming, he alleged that the PHIUS group were not using the "proper" documentation to certify projects. “Evidence of PHIUS’ certification of Passive House buildings without the requisite documentation has threatened the integrity of the Standard and forced PHI to terminate PHIUS’ status as an accredited Passive House Building Certifier,” said Feist.

Feists' intepretation was that given the precision of design and implementation to officially certify a Passive House, which is around 10 time as efficient as code, the possibility that the US Passive House certifying agency were not properly complying with the standard could undermine the entire program. Feist continued, “PHI is doing everything in its power to ensure Passive House’s continued success, especially in the US where we will continue to reach out to those competent, motivated and fair actors who emphasize real work and real Passive House construction.”

At the heart of PHIUS’s original disagreement with PHI was the number of different climate zones in the U.S. that Passive House design had to cope with. Applying the fixed energy criteria in Passive House design that was originally developed for Germany’s climate, PHIUS claimed, was absurd in either a subtropical climate or an extremely cold climate.

PHIUS has since built its entire Passive House standards and certification programs around accommodating these climate differences, using elaborate calculations to determine what is practical and cost-effective for each specific climate. The idea is that owners should not have to invest in design features like thicker insulation that offer diminishing returns in more temperate climate zones, just to meet what PHIUS views as an arbitrarily fixed energy target as calculated by the PHI with their PHPP software (Passive House Planning Package). We will say this, that does seem a logical approach to optimum efficiency in Passive solar design.

Is PHIUS Passive House certification easier? or PHI certification? It depends...

It is often said that PHIUS is easier to achieve than PHI, but this is a broad overgeneralization. Certain objectives may be easier, others may be harder. It all depends on the scale and location of the house in question. PHIUS is definitely more adaptable than PHI but does that make it better? Perhaps the real question ought to be why we aim for Passive House certification in the first place? Is it for the prestige and exclusivity of the certified Passive House label or are we genuinely hoping to reduce CO2 emissions and our overall ecological carbon footprint? Wouldn’t it make more sense to encourage the maximum number of buildings to achieve a certain threshold of energy efficiency rather than creating a very narrow path for very few? Passive House certification or indeed LEED Certification, is still seen by many as an "elitist" club reserved for the wealthy. In many ways that's why EcoHome designed and built The Edelweiss House - a Passive House Standard, but LEED V4 Platinum certified home built at the same cost as a standard North American home... Read more here.

Does a Passive House have to be certified?

The most energy-efficient buildings are those designed to harness and retain heat from the sun in the winter, and employ shading techniques to passively keep homes cool in summer. Through the Passive Solar Index program, Ecohome helps designers achieve their performance goals and offers them recognition for their efforts - regardless of onerous and potentially costly Passive House certification.

Does the world need another home rating system? No, probably not, but thankfully, this isn't one.

This is a service we provide where building envelopes are optimised for home building professionals or homeowners by Passive House & LEED trained engineers to provide a clear sense of how their homes will perform, and where improvements are best made to save money and energy - a balanced approach to building better homes accessible to all. A typical home in Canada or colder climate zones in the USA will consume over 100 kWh per square meter. To encourage energy efficiency, any home that achieves below 50 kWh will be featured on our PSI pages free of charge, EcoHome's mission is to help anyone, anywhere, build a better more energy efficient and healthier home that they can afford, that's why we encourage every reader to subscribe to The EcoHome Network here, and ask your own questions about efficient home construction and renovation. You might also choose a Prefab Passive House & LEED Kit Home which are for Sale for delivery in Ontario, Quebec, New York, Vermont, Maine or New Hampshire. Now, back to Passive House certification.

PHI and PHIUS Common ground:

The Passive House concept is based on three ideas that both certifications share. First off, a fabric-first approach to reducing heat loss through the building envelope achieved through thermal bridge-free construction, super insulation choices and airtight construction. Heat loss through the envelope not only hampers a building’s energy efficiency but can also bring about damage to its components (via condensation caused humidity and mold or mould).

The second principle is to optimize and balance energy gains by, for example, strategically placing the windows. The goal is to optimize solar heat at key moments of the day while avoiding the building becoming a furnace once the setting sun reaches deep into the house (balance). Choosing the right windows for a Passive House is key. Heat gain mustn’t be offset by losses caused by badly insulated glass or air leakage due to poor window frame installation (see how to improve window installation for Passive House here). The third theme is efficient systems. After all, the best way to make energy savings after properly insulating is by choosing & installing high efficiency home mechanical systems (air exchanger, appliances, heating, water heater and lighting) that are incredibly efficient to begin with.

These are the building blocks of both PHI and PHIUS Passive House certification. The primary goal of both bodies is the same - to design buildings that use next to no energy. The point where they diverge is in how they evaluate the performance standards.

Passive House Institute performance standards & the difference with PHIUS certification:

The PHI standards are clear, precise and set in stone. One size fits all. We’ll get into the nitty-gritty below but to summarize :

Airtightness : ≤.60ACH50 (Air changes per hour at 50 Pascals)

Heating/Cooling : Annual consumption ≤ 15 kWh per square metre of living space (Treated Floor Area) in heating and cooling OR a peak demand of ≤10 W per square metre of living space (TFA) Primary Energy: Annual consumption in Primary Energy ≤ 120 kWh per square metre of living space (TFA)

Primary Energy: Annual consumption in Primary Energy ≤ 120 kWh per square metre of

living space (TFA)

What does all that mean? The airtightness of a building is calculated by measuring leakage - the volume of air (in cubic feet per minute, CFM) entering a building pressurized at 50 Pascals and dividing that measurement by the net air volume of the house. Simple enough. But does it make sense? After all, air leaks happen through a building’s shell (the surface) and two buildings with identical volumes may have entirely different surfaces.

One wouldn’t estimate how many gallons to buy to repaint a room by calculating the room’s volume. And like in painting, when it comes to air leakage, it’s all about the square feet of the surface. Growing a geometric shape affects surface and volume differently. Volume, with the added dimension of depth, grows exponentially as the building grows, so dividing the air leakage by the volume as opposed to the surface of the building makes it far easier for bigger buildings to achieve the standard. The Passive House movement is, in essence, an ecological one, so if buildings are not going to be measured by the same yardstick, should it not favour those of more modest proportions?

PHIUS+ uses a different standard, moving from ≤.60ACH50 to 0.05 CFM/square foot of surface area. It starts with the same metric - the total air leakage measured in CFM, but it divides it by the total surface area of the building.

As for heating and cooling load standards, PHIUS again takes exception to PHI’s approach. The number of kilowatt hours permitted annually as well as the number of watts in peak load were established for German climate realities (the birthplace of PHI). The standards are well-suited to central Europe’s modest temperature variance and humidity levels but don’t work in other climates.

PHIUS’s engineers - struggling to establish the program in North America - quickly realized that expecting a building in the Yukon to have the same annual heating load as a building in Hawaii just wasn’t realistic. That is why, in collaboration with the Building Science Corporation and the US Department of Energy, PHIUS established new “climate-specific” targets that are tailored to their locale. A fairly exhaustive map of North American locations and their targets is housed on the PHIUS website, but here’s a little snapshot:

|

|

Passive House certification comparisons between PHIUS & PHI standards in different climate zones

|

* PHIUS and PHI calculate living space somewhat differently. PHI calculates Treated Floor Area (TFA) while PHIUS calculates interior Conditioned Floor Area (iCFA). Each standard excludes interior elements of the building or calculates them as a percentage of the living space.

A Passive House owner in Juneau gets to use more energy heating their home than a homeowner in El Paso, while the Alaskan has a much smaller allowance in the cooling department than their counterpart in the south.

Were one to give a pair of sandals and a pair of winter boots to an Alaskan and a Hawaiian, would it be reasonable to expect them to use each pair for six months of the year? If an equivalent amount of energy and resources went into creating the pair of boots and the pair of sandals, why not allow the Yukon resident to wear his boots eleven months of the year and his sandals for one month while allowing the Hawaiian to do the opposite? In the end, is it more important for the planet that they use the same amount of energy or that they use their allotted energy in an identical fashion?

As for Source Energy, the important thing to understand is that we’re talking about energy at its source. The bulk of energy gets lost in transport - up to two thirds of it here in North America. For every three kilowatts that leaves the power plant, only one makes it to the house. PHIUS calculates that ratio, what they call the Source Energy Factor, at 3.16. PHI, again based on EU data, sets that ratio at 2.6 worldwide (pretending the North American grid is 20% cleaner than it actually is - a curious practice for a standard aimed at carbon reduction).

In normal circumstances, this factor grows or shrinks depending on how dirty (coal, nuclear) or clean (hydroelectric, wind) the energy is, and how vast the network is (e.g., a hydroelectric dam may be hundreds of kilometres away from the houses it supplies). Because this factor varies so much depending on one’s location and energy source, builders lobbied PHIUS to tailor the standard according to the energy source. PHIUS’s response was to change the whole equation. Rather than evaluate consumption on a per square metre basis they made it about how many people live in a house, deeming the reduction of CO2 emissions a responsibility to be shared by every person (no matter what their project or energy source).

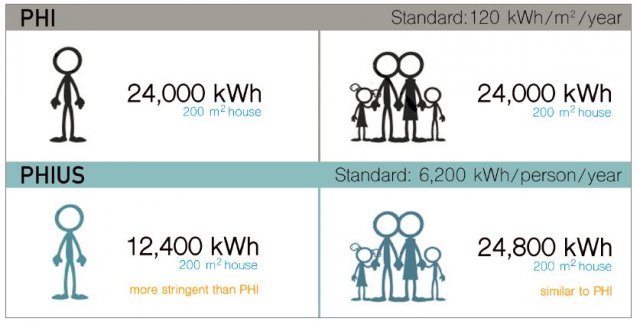

PHI’s standard of ≤ 120 kWh/metre2/year became PHIUS+’s ≤ 6200 kWh/person/year. The number of residents is counted as the number of bedrooms plus one. For non-residential buildings the ≤ 120 kWh/metre2/year metric remains in effect. This way of calculating gives “right-sized” projects a distinct advantage because it makes it very difficult for someone living alone in a mansion to hit the targets.

|

|

Passive House certification comparisons PHIUS v PHI standards in terms of residents or sqft

|

Over the next few years, PHIUS aims to gradually reduce the standard to ≤ 4200 kWh/person/year, lowering the threshold for a single resident to 8,400kWh and to 16,800kWh for a family of four. The only renewable energy that PHI’s PHPP software allows for is solar-thermal energy (e.g., solar hot water). All other renewable energies are disqualified - something PHIUS changed by including on-site energy production (photovoltaics or wind turbines) used on site in their assessment.

PHI and PHIUS both believe that the Source Energy Limit should be the the most stringent but PHIUS’s is based on the number of residents rather than on square footage of living space. This doesn’t make the standard easier to hit. It actually makes it harder. The fewer the number of residents and the bigger the living space, the more challenging it is to achieve the standard.

Passive House Certified products:

Another problem PHIUS has with the PHI method is their certification of air exchangers (HRV and ERV). PHI set up its own proprietary method of evaluating air exchangers to make an enlightened choice between HRV & ERV and among certified models. If, however, one wants to use a model that hasn’t been evaluated (aka not PH-certified) PHI uses the manufacturer’s specifications and cuts 12% from its efficiency. PHIUS’s Technical Committee frowns upon this practice, deeming it unfair discrimination against some very efficient machines simply because they aren’t PH-certified which obviously involves a cost.

North America has its own certification program for air exchangers, done by the Home Ventilation Institute (HVI), so PHIUS launched its own modelling protocol incorporating the best elements of PHI and HVI to make more available models eligible. The goal was not to dilute the standard but to give builders more paths to certification.

There’s nothing wrong with builders preferring one Passive House certification over another, or even one Green Building certification over another. PHI, PHIUS, LEED, NetZero, Zero Energy, Novoclimat, Energy Star, Living Building Challenge all have their raison d’être and were all created with the intention of easing the stress we’re putting on the planet by pushing the industry toward environmentally sound, super-efficient construction. If their objectives are indeed the same, why not redirect the energy spent debating the merits of one over the other into finding solutions together and making healthy, high performance buildings that are accessible to all?

Enjoyed this article and hope you keep updating it.

Interesting piece. Energy Vanguard had some nice history on the actual orgins of Passive house, that dove a bit deeper if anyone is curious to learn more. I built my first Passive House in my 30s, and ended up working at a Passive House window + door manf here in Boulder, Colorado. :)

Cheers, Brian