First, the background to this Passivhaus

My partner and I are geeks. Our idea of a romantic dream was to build a house so well insulated you could heat it with a hairdryer. For added fun, we wanted to do this on a tight budget while raising a young child.

The hairdryer part wasn’t a pipe dream – it’s a common way of describing the Passive House certification standard or Passivhaus, which is the building code in much of Germany where it originates. It’s also mandatory for new construction in many European cities. Yet, even though it can cost as little as 5 percent more than a conventional house to build, there are just a handful of Passive Houses in Canada, where winter doesn’t appear to be a passing trend.

|

|

The living and dining area of Ann Cavlovic's Passivhaus House © Mark Rosen.

|

These were the kinds of facts I used to recite when people looked at me quizzically; the term “Passive House,” without further explanation, seems to make people visualize a house that will fall down if you punch it. Others confuse it with “passive solar” houses from the 1970s, which often had too many windows, causing wild temperature swings from day to night.

“There’s no good reason,” I used to say, “why we don’t build more Passive Houses in this country.” I assumed it was just Canadian denial of our climate; we like to wear thin jackets and complain about the weather. Are we this way with our permanent shelters too?

There are indeed no good reasons. But there are reasons.

Our Passivhaus design was engineered

We initially thought ourselves lucky to meet an engineer with impressive Passive House credentials. After months of discussions, he presented us with floor plans, which, to our eyes, looked dreamy and wonderful.

Then we showed them to friends. When enough people with design backgrounds used words like “dungeon” and “bunker” we had to accept we were in trouble.

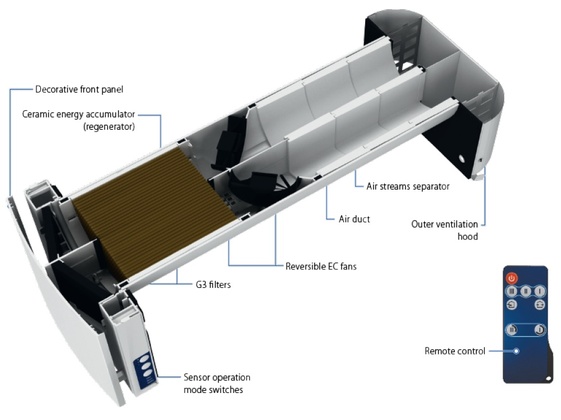

Normally, building a house involves two experts: an architect and a builder. In a Passive House you need a third: a certified Passive House designer, who uses a computer model to determine whether you meet the standard or what you’d have to tweak to get there. To do so, there are six “usual suspects” to play with. The most obvious include thickly insulated walls, window placement to make good (but not excessive) use of the sun’s energy, and tightly sealing all cracks. Less obvious, perhaps, is the minimization of “thermal bridges” such as concrete balconies – like those jutting out of most condos that siphon heat out of the floors all winter long.

A super-duper heat recovery ventilator is necessary to bring in fresh air while minimizing heat loss. And finally, the structure’s surface-area-to-volume ratio needs to be minimized. None of this involves space-age materials (you can use regular insulation, although an über amount of it), although North American suppliers of Passivhaus high quality windows, tapes, and equipment have been slow to emerge.

The key word in all this is “design.” A certified Passive House designer doesn’t necessarily know much about aesthetics. It should ideally be an iterative process, a tango between an architect and a Passive House designer. But many early European projects were only “designed” by Passive House designers, who are often engineers, not designers in the usual sense. So unfortunately, Passive Houses have a reputation for being reminiscent of Cold War era communist housing, or something made by a structural engineer who’s never kissed another person on the lips.

Change of plan - where art thou passivhaus architect?

Extricating ourselves from arrangements with the engineer wasn’t costly, but we’d lost a lot of time and emotional investment. Any building project, let alone green ones, obliges you to get back on the horse after frequent bucks. This was but our first.

When we started looking for an architect, we were surprised by how many were keen to design a relatively small eco house. However, finding another certified Passive House designer wasn’t easy. And certain ones in our region had been involved in a conflict that led to an infamous divorce between the German and U.S. Passive House Institutes.

But then someone new came on the scene – a firm in which one architect had just been certified as a Passive House designer. Aesthetics and energy-efficiency could reconcile their creative tensions in-house. These architects were young and their business almost brand-new, but there’s an important flipside to a lack of experience: a lack of baggage. They hadn’t yet pissed off a single person. We signed a contract.

There should be therapists specializing in construction-related couples’ counselling. Building, like renovating, tests every trigger point in a relationship: money, burden sharing, and stress management. For us, the triggers detonated about fifteen minutes before we met the architects for the initial “get-to-know-you” sessions. We arrived at their office, politely expressed how we dreamed of living, while only partially concealing our desire to strangle each other.

A few weeks later they gathered us around a table and presented their design on slick laptops using 3D modelling, with shadows falling as they would at 2:30 pm during winter solstice. Rather than our crankiness, their design was inspired by the raga and drone in Indian classical music, which they felt reflected our need for both individual pursuits and the constant hum of family life. We had left the domain of the utilitarian geeks and leapt right into that of the artsy.

|

|

A beautiful Canadian Passivhaus design © Mark Rosen

|

Their design was stunning – and tens of thousands of dollars over budget. This was due to a miscommunication only possible with a Passive House: when we’d said we could afford so many square feet, we were thinking total footprint, but they were thinking internal dimensions. The difference is negligible in conventional houses, but not in a house with almost two-foot thick walls.

But our architects defied the stereotype – they had small egos and several non-black articles of clothing – and went back to the drawing board. We soon had a smaller but beautiful design even our friends approved of. Maybe there was some raga and drone in there, we didn’t know, but we sure loved it.

So, who was going to build our passivhaus?

To keep costs low, we wanted to finalize the plans after getting some “reality checks” from a builder who actually swung a hammer. As with the architects, the builders I called seemed keen to work on a small house. But the enthusiasm ended once I explained the Passive House element. “Why the hell would you do that?” said one. Another told me I must be “quite crazy” to try that in our climate; it would look like a Flintstone house and attract mould. Another schooled me on how extra insulation is useless (a valid point in a conventional house with thermal bridges but not in a Passive House). Nor did any of them appreciate the inference that there was a “better way” to build than they’d been doing for years.

Eventually, we found a builder who had completed some near-passive house projects. After bribing him with a free lunch, we met at a pub where he leaned back in his chair, exhausted, repeatedly mentioning he hadn’t seen his wife or kids in ages. His current Passive House projects were draining, he complained, because he had to constantly police his carpenters who didn’t want to bother with details like using specific draft-sealing tapes in specific places. He’d recently had to open up a wall and restart because they’d skipped a few steps. He was spending so much time on-site that he was neglecting the management of his business. As a result, he didn’t think he’d make any money this season. Despite all this, he wasn’t sure his projects would meet the standard, as the certification process was so onerous.

Basically, he was one burned-out dude. With zero enthusiasm he said he could build a house for us but couldn’t guarantee it would work very well.

It was around this stage I started fantasizing about driving to a model home in the suburb of my least affection, and choosing from an existing palette of floor models, paint schemes, and conspicuous consumer upgrades. For a granola type like me, this was extreme. But no one would call me crazy. I’d feel so normal. I could forget that it’s often these carelessly-built tract homes, even if built “to code,” that develop mould within twenty years.

When I was 8 years old my friend Chantelle died of leukemia. Her parents had recently had foam insulation sprayed into their walls, a type that was subsequently banned for containing carcinogens. No one could prove the foam was the cause of her cancer specifically, but even as a child I could make the link. After she died, the company sucked the foam back out of the house at its own expense.

It’s a wonder, then, that I craved walls with the thickest insulation imaginable. Although we planned to use blown-in cellulose insulation – basically plant fibers resembling shredded newspaper, one of the oldest and safest insulating materials around – still the fear of doing something “different” resurfaced in remembering Chantelle. So I began to empathize with builders who had an aversion to new techniques. Mistakes can happen in any project, but the risks increase when the depth of experience is shallow. And Passive Houses are certainly not immune: in one project in Belgium the insulation and ventilation systems were improperly installed, leading to levels of mould and formaldehyde (from the wall sheathing) that rendered it uninhabitable. There is simply less room for sloppy technique in a high-performing, Germanic house.

So maybe a Canadian shivering in a thin winter jacket has a point after all. Maybe they once had a warm coat, but it gave them hives, so they’re sticking to the leather jacket that’s tried and true. They just need proof that warmer options exist, are safe, and don’t look like a hemp sack. I still hoped that’s what we could achieve.

During all this, I attended a conference on climate change. The panel spoke about the things that need to change in our society: the ways we transport ourselves, grow food, generate energy, and yes, build structures. Although I’d heard most of this before, I sat at the back of the room and felt the weight of this ‘inconvenient truth’ more palpably in my bones. For the first time, I was trying to lift something with my own hands, instead of just making relatively easy lifestyle choices or pointing fingers at government.

But others still carry most of the weight. Building a sustainable house is our small contribution, and nothing I’d been whining about is as inconvenient as tearing up coal plants or pushing transit through a city designed around cars. Stuff has to move. It can’t wait twenty years. So this is how my family and I will take one for the human team.

In other words, pig-headedness won out over anxiety. Neither my partner nor I had been early adopters of anything before, but we weren’t about to build a fossil-fuel guzzling house just so that a carpenter could have more room to screw up. So get back on that horse, I said to myself, as I signed a cheque for the architects and an international certifier to chaperone the eventual build process. Life is a constant application of the creative forces of the sun against entropy on earth. That’s solar radiation physics for: “Suck it up, princess.”

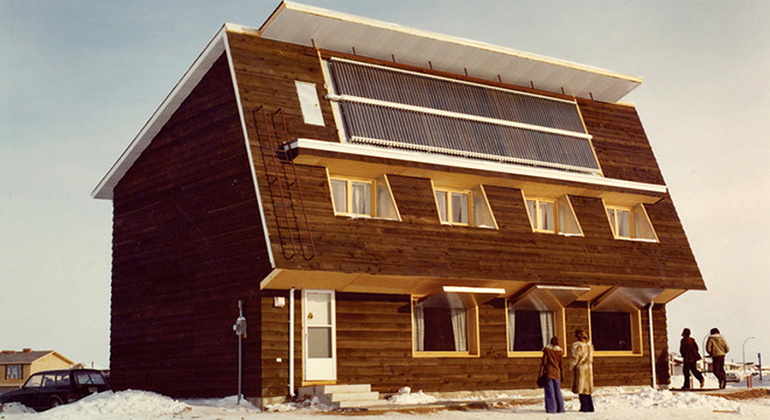

Eschewing the safe and mediocre might seem atypically Canadian. But let me dispute that stereotype by noting that the Passive House standard has Canadian roots. During the 1970s oil crisis, the Saskatchewan government asked Harold Orr, an engineer, and a committee of keeners to design a passive solar house appropriate for the local climate. The result was the world's first Passivhaus - The Saskatchewan Conservation House, which not only incorporated passive heating from the sun, but also many of the elements that make up the current Passive House standard: careful sealing with tape for air-tightness, jaw dropping amounts of insulation, and a fresh air intake and heat exchange system designed from scratch (spawning a company that still exists). It was no solar hippie house.

|

|

The first Passive House - Saskatchewan Conservation House Image via the Saskatchewan Research Council

|

But when the oil crisis was over it was largely forgotten. Subsequent owners were unaware of its importance and removed features that were imperfect first attempts in the right direction, like awkward window shutters meant to compensate for the flimsy windows they had to settle for. The Germans didn’t forget, however. Wolfgang Feist, one of the two physicists who created the “Passivhaus” standard, credits the Saskatchewan Conservation House for its inspiration.

Some Canadians do wear a proper winter coat

Or maybe that’s just in Saskatchewan?

Because I was clueless about what “timber framing” means, I called the person with whom we eventually built.

Timber framing is how most Europeans built houses until the 1800s. Four or more heavy logs provided structural support at each corner of the house, and light walls were built between them. It fell out of fashion mostly because a new stud frame method – in which the wall construction also provided the structural support – was cheaper and required less skill to assemble.

Building a stud frame wall initially involved a bunch of two-by-fours standing two feet apart, connected at floor and ceiling by nails instead of the more labour-intensive “joinery” used in timber frames. A flat backing such as plywood stabilized all this and created rectangular cavities into which insulation could be shoved. (In my former 100-year-old house, that included newspapers, socks, and other unmentionables.) Mechanical ventilation wasn’t necessary, since the whole contraption leaked so much air you didn’t have to worry about air quality or mould. After the oil crisis there was pressure to insulate better, so the industry moved to two-by-sixes to get two more inches of wall depth. But every wood stud was still a thermal bridge that continually leaked heat – in nearly every North American home only about two-thirds of a wall is actually insulated.

Passive Houses usually get around this by building two stud frame walls back to back, with a continuous layer of insulation in between. But with a timber frame there’s virtually no limit to the thickness of a wall one can hang on the structure. Plus, building one thick wall is cheaper than building two thinner ones, which offsets the cost of the timbers. So timber framing is an old-fashioned method that’s arguably better suited to modern building science. I’m glad some carpenters stuck with it, despite being out of fashion for 200 years.

And this builder wasn’t burned-out. In fact, he seemed excited about trying something new. Most importantly, he was a rarity for having a long-standing crew of skilled carpenters who hadn’t lost their pride in artisanship. And accommodating two timber posts in the middle of the house required little design adjustment. So our choice was made. When I gave the builder a deposit, we both brimmed with positivity. He nevertheless added, “But still, by the end of any project, I never want to speak with the client again.”

This bit of honesty was actually a gift for building

Building any house is an exercise in problem solving, decision fatigue, regret, and sorrow. The most resilient embrace each blow to the head, and the wallet, as an “opportunity” to overcome a challenge. Our tendency was more toward ugly tears. But surprisingly, only a small portion of those “opportunities” were linked to the Passive House elements of the house.

Screw-ups will happen during any project. If your tradespeople are skilled and conscientious, as ours fortunately were, screw-ups will still range from the minor to the moderate, as a simple function of moving from what works on paper to how life unfolds in practice. Aesthetic screw-ups we could live with. What haunted us was wondering what was different enough about our anal-retentive house to make a screw-up more consequential, whether that meant not meeting the standard, or worse, something that would jeopardize our health or safety.

When a suspected issue arose, we’d fire off an email to the builder and architects. This became a race to see who’d be the first to throw the other under the bus. The builder would say the plans from the architects weren’t detailed enough. The architects would say the detail was on page A4.2 if the builder cared to read it. Because the issues were technical, we couldn’t decipher who was “right.” I began to feel like the child of divorced parents. ‘I love you both. Can you kiss and make up?’

But in fairness, I should be objective about what kind of clients we were: friendly, cooperative, detail-oriented, and prone to anxiety or even borderline personality disorder about mold, structural failures, and other catastrophes. Or more succinctly: nice but not infrequently pains-in-the-ass. We were once told that my partner’s repeated emails about tiny gaps in the foam under our foundation, which turned out to be a non-issue, cost $200 in project management time. This wouldn’t be the last. There were certainly mistakes we “caught” to good effect, but they amounted to about 5 per cent of the things we worried about.

Our passivhaus is risen

Yet slowly, a house emerged. Any “deficiency” the architects reported was sneered at by the carpenters at the end of a scorching summer day, but fixed. Our carpenters took pride in their work, which is far too rare these days yet crucial for any high-performance building. They practically stalked the electrician, plumber, and other sub-trades to ensure no unplanned holes were poked through the air barrier. As a result, the blower-door test proved the house met the air-tightness requirements, which is no small feat.

Near the end, passers-by would holler out, “Nice house.” Much like the process of having a baby, we took great pains to ensure the health and safety of our creation, and then only wanted to hear how darn cute he was.

And cute isn’t superficial. As our architects point out, we take better care of things that are beautiful. An ugly or trendy kitchen will get ripped out, landfilled, and replaced sooner than a simply beautiful one, with all the attendant environmental impacts. To make our house, or any Passive House, something people might desire and care for over many years, beauty is a very practical requirement.

|

|

Passive House Design, it's all about attention to detail to make a house work © Mark Rosen

|

I’m completing this essay in the writing nook designed for me. I look out through three panes of glass at a row of trees, a west-facing view that casts the perfect light for writing. It’s going to be a scorcher of a summer’s day, but we’re letting the cool morning air blow through before closing the windows and turning on the ventilation, keeping us cool without air conditioning. Last winter, we used one electric baseboard heater on cloudy days and otherwise relied on the low-angled winter sun to add heat to a house that barely lets it escape. On the first brutally cold and sunny day after we moved in, I sat beside our south-facing window in a tank top.

And energy-geekiness aside, we just love our home. Comfort isn’t only about the reading on the thermostat; our bodies perceive gradients in temperature across different parts of the skin, which is why I wore a fleece in my drafty old house when the thermostat said 21°C whereas here I’d be in a t-shirt. The indoor air quality is so much fresher too. Aesthetically, the house doesn’t fit us like a glove; it fits our better selves, since we hang out with each other in more positive ways – we often linger at the dining table playing a board game, something we’d never do in our old house, mostly because that space was drafty and uninspiring. In the end, the marriage of old-fashioned timber frame and modern architecture is the perfect balance for us soft-core hippies. Mom and dad worked it out after all.

Our own relationship survived as well – no small triumph, that. Our son, who “helped” in little ways, yelped for joy on moving day.

Visitors seem surprised that our “eco” house doesn’t resemble a mushroom. And in winter, most are shocked that we only have one little heater and yet the concrete floors aren’t cold. After a tour, they typically ask, “Why doesn’t everyone do this?”

There are indeed no good reasons. I hope, very soon, there will be no reasons whatsoever.

To read more about passive house standard houses see here, to see more details on Architect designed prefabricated Passive House & LEED ready Kit Homes available in Quebec, Ontario, New York, Vermont, Maine or New Hampshire here or see this Guide about Passive House Certification in North America here, from the EcoHome Green Building Guides on North America's favorite green building website - EcoHome.net...

Ann Cavlovic is a writer living in the Ottawa area. Her fiction and essays have appeared in several Canadian journals and newspapers including The Fiddlehead, The Globe and Mail, and PRISM international. Find her at: www.anncavlovic.com. Article first written in Canadian Architect Magazine,

how much was the total cost?

Ann I love your article. I am 35 days on to building my first earth conscious home with L.E.E.D and Passive house in mind. No one wants to support it in practice but only in theory. We are on our 3rd architect. Your article gave me hope too keep going.

How many sq ft is your home and how long did it take to physically build it? Thanks!

Hi SD,

Cost depends on many factors, and price per square foot is not the best comparison for a smaller than average house. Nonetheless, all things considered, I do think 5% above a conventional build was in the right ballpark for our case.

Hi Holly,

Thanks for the feedback! The home is about 1200 Sq. Ft. (no basement) so efficient use of space was key. Our build was relatively fast - wall panels were built offsite in late winter. We broke ground in June, and moved in by early December.

Hi Ann,

Wonderful article! My wife and I are looking to build a passive house west of Ottawa and we're curious what builder you went with?

Hi Matthew, I don't know if Ann sees the comments here very often, but the builder was Lester Perrault of Woodenshoe timberframes in Wakefield, Quebec.

That may be out of his range, if so we may be able to steer you towards other Passive House builders, but I would also suggest you have a look here at prefabs , the controlled atmosphere of a manufacturing facility can lead to top quality workshmanship at better prices. We will have page up in a couple of days with a lot of models to choose from, so either check back soon, or sign up on the link on this page and you'll get an email notice.

LEED and Passive House ready prefab kit homes for Canada and US

Thanks for chiming in Maurice. Good luck with the build Matthew.

Hi Ann, can you provide the Architecture firm name here? I would like to contact them as well.

Thanks

Zach

Hi Zach, that would be Mark Rosen.

PlotNonPlot were the original architects. Mark Rosen is now operating independently via beinc.ca.