As founder of the Resilient Design Institute, Alex Wilson is an internationally renowned authority on resilience in home design. Beyond just homes, 'resilience' can in a way describe a lifestyle, or perhaps a life philosophy.

Sure, 'green' homes can help save the planet, but some of them may also save the individual. Predictions for the future vary from the ignorantly blissful to the apocalyptic, so it's hard to say exactly how things will look a few generations down the road, but there are a few things we know for sure - the climate is changing, disastrous weather events are becoming more frequent and severe, resources like energy, food and water are becoming more and more scarce in some areas, and a growing world population means more and more people want a piece of that shrinking pie.

To be able to offer your family a safe, warm home and enough to eat without relying on societal infrastructure is what defines resilience. After a lifetime of teaching it, Alex Wilson recently had the opportunity to put his knowledge into play. The following page chronicles that experience, hope you enjoy.

Two years ago, when I launched the Resilient Design Institute, was a time of transition. I was pulling back from BuildingGreen, the company that I had started in 1985, and my wife, Jerelyn, and I had just bought an old Vermont farm a third of a mile down the road from where we had lived for 30 years. We were beginning what would be a long process of figuring out what to do with the house and property.

Indeed, the house planning, design, and reconstruction was a major undertaking. After having written about energy efficiency, renewable energy, and green building for more than 35 years, there were countless ideas, materials, and innovative products I wanted to try out. This would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create a model of sustainability, accessible design (where we can age in place), and resilience.

Renovating (really rebuilding) the house cost a lot more than we had anticipated and took a lot longer than expected—a nearly universal complaint of those involved with such projects—but we are very happy with the outcome.

We moved in around the first of January, 2014, just in time to give the superinsulated house a real test in what would turn out to be one of the coldest Vermont winters in decades. We found that, indeed, the single, 18,000 Btu/hour, air-source heat pump was able to keep the house comfortable; we only used our back-up wood stove eight or nine times to supplement the point-source heat pump or provide the ambiance that only a wood fire can provide.

This ability of a house to maintain reasonably comfortable (safe) conditions on the coldest winter nights—even if power is lost—is a key tenet of resilient design, and I was very pleased that our house did so well. Though we hope the house to be net-zero-energy in its operation—with space heating, water heating, cooking, and almost everything else, powered by a 12 kW solar-electric system—we can heat the place just fine with our small wood stove if we need to.

Moving our focus outdoors

As the cold of winter gradually ceded control to the sunshine of spring, I was only too ready to turn my attention to the out-of-doors.

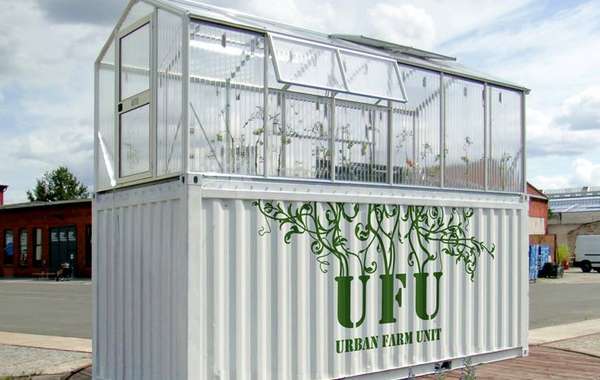

I had been thinking a lot about resilience and what exactly that meant for a rural landowner. We had done a good job with the house, and we are planning how to provide water during power outages—likely using a modern hand pump of the type I’ve written about—but resilience is also about food.

I wanted to create a homestead with the capacity to become close to self-sufficient in food production should circumstances call for such a need—for example, if a long-term drought in the West and Midwest with no snow pack in the Rockies and Sierras curtails agricultural production in the grain belt and California’s Central Valley. In such a scenario, the supply-line of grains, vegetables, and meats from points west becomes compromised—not a likely scenario, but a possible one.

How could our land at Leonard Farm provide some level of food self-sufficiency?

|

|

© Alex Wilson

|

Comments (0)

Sign Up to Comment