There has been a steady evolution in the way we build homes over the last couple of decades, and the old standby wall recipe of 2x6s, fiberglass insulation and polyethylene doesn't measure up anymore with building codes, nor the trend towards high performance housing.

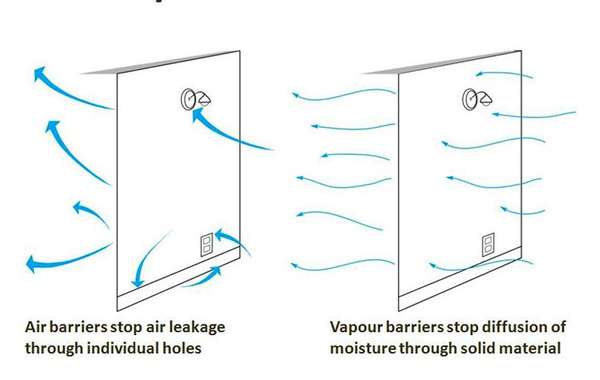

One aspect of wall assemblies that is garnering some well deserved attention lately is how we control the migration of moisture. A polyethylene vapour barrier is one way to do it, but it's the old way to do it, and not necessarily the best for this climate, particularly with air conditioned homes.

Whether or not a material qualifies as a vapour barrier is determined by the amount of moisture that passes through it, and it is given a rating. Any material that allows less than 60NG (nanograms) of moisture to pass through under specific conditions, is considered a type 9 residential vapour barrier by the National Building Code.

Including a vapour control measure on the warm side of the insulation is essential for preventing moisture movement through walls in winter, and the ensuing damage that comes with it. In summer however, with the combination of hot, humid days and air-conditioned, dry interiors, the vapour drive reverses and can force moist air inwards through your insulation where it can condense on a cold and impermeable vapour barrier.

Ideally we'd have no vapour barrier in summer; but short of that we should at least have one that allows as much drying to the interior as possible without sacrificing its winter performance. So the closer your vapour barrier is to 60NG, the better. For the sake of context it should be noted that polyethylene is rated at 3.4NG.

People also often ask the question which is better, OSB or plywood for roofs, walls and floors? Well ecoHOME would reply "it depends where, and what other materials you are using!"

Rated at 40NG, 3/4 inch OSB sheathing can be one of the better vapour barriers for home construction in most of Canada. But in order to act in that role, it needs to be on the inside.

Sheathing provides a necessary structural strength to house frames, but it is written nowhere except in our minds that it has to be on the outside. When installed on the inside it still provides the structural strength, but can additionally act as both an air barrier and vapour barrier.

There is no question that this technique also presents a new challenge to the builder, namely the fact that you have exterior rather than interior cavities to fill with insulation. But this can easily be overcome with foresight and planning,

Th main photo above and the following wall description are of a project in Val des Monts, Quebec, built by Wakefield Construction.

Wall assembly from the inside out:

- Drywall

- Horizontal 2x4's (on edge) as strapping, to allow for wiring chase without penetrating the air barrier

- 3 / 4 inch OSB sheathing (with taped joints)

- 2x8 studs with mineral wool batts in cavities (R28)

- 4 inch wax-impregnated wood fiberboard on the exterior to provide a drainage plane, break the thermal bridge (R13.4)

- Vertical strapping (if your cladding requires horizontal strapping, be sure to do a vertical layer first to allow for drainage)

- Cladding

This is not some theoretical untested wall system, the technical specifications of 3/4 OSB meet the requirements of building codes for both air and vapour permeance. By moving the sheathing to the inside, you are simply letting it live up to its full potential as an air barrier and vapour barrier, and eliminating the need to install a separate product to do that job.

One of the benefits of OSB as an air barrier is that it is solid. A polyethylene or foil air barrier can be easily pierced by the slightest touch with a sharp tool, without even realizing it. In contrast, it is unlikely you will put a hole in an OSB air barrier that was not intentional, or at least unnoticed.

Blower door tests

The air seal of a building is measured in ACH (Air Changes per Hour), and is determined by a blower door test where the building is depressurized by a fan in the door, and air leakage is measured.

The average home built to code using conventional building practices is expected to have air leakage rates of 3.5 ACH, which under normal air pressure conditions means the entire volume of air in a home will have leaked out and been replaced 3 or 4 times every day. Using this technique of interior sheathing on previous buildings, Wakefield Construction has achieved ACH results that are a fraction of that, as low as 0.4 ACH.

There is a common misconception in the building industry that a house can in effect be too tight. That is completely false; the tighter the better. You need fresh air, but it should be supplied by properly balanced heat recovery ventilation, not arbitrary holes in an air barrier. Always seal your home as tight as you possibly can and let your air exchanger do the job it was designed to do.

Ordinarily there is a lineup of drywall crews, plumbers, cabinet installers, electricians, heating and cooling contractors, all waiting their turn to punch holes in your air barrier, perhaps not realizing the importance of properly sealing those breaches afterwards. Because of that unfortunate reality and a general lack of prioritizing air barriers in the industry, under normal air pressure conditions the average brand new home can expect to have its entire volume of air leaked out and replaced 3 or 4 times per day.

Along with focusing on techniques for preventing air leakage, some thought needs to go into products as well, and how they are best applied. Worth noting is that most commercially available building tapes contain solvents that evaporate and eventually become brittle and peel. The most durable tapes on the market contain no such solvents, so they actually do the job they were intended to do. They won't come cheap, but they work.

Interesting; hadn't seen this technique before and bears thinking about. If moisture is getting into the wall though (possible even with HRV's) not sure damp OSB on the inside of the wall is a good thing. As far as poly VB I think you could mention that this is one way to dispense with it, there are others, closed cell spray foam insulation for example (not my favorite product, but no poly required in my area anyway).

No, damp OSB in your wall is not a good thing. But moisture going through you wall in any place is not good, and any moisture that does get into you walls will be moving one direction or the other (most often out) so it will in most cases run into OSB sheathing anyway.

And with poly in your walls, a hot summer and air conditioning is a very dangerous combination for moisture damage. What this system does is just allow the wall to dry better in both directions than it can with poly.

Anytime you introduce something this new to the industry it always causes some head scratching, which is a good thing. We need to think and talk more about what we are doing in our walls so I really like that whenever I present this system it usually ends up in a great discussion.

The biggest problem with this is that we are so accustomed to using poly that it is hard to imagine a wall without it, despite the fact that building scientists strongly recommend avoiding it to STOP moisture damage in walls.

And you are right, spray foam is definitely a great performer, it is highly unfortunate that it comes with a pretty heavy ecological footprint. Though I have heard word that new blowing agents could be on the way in the near future that will greatly reduce that. Thanks for weighing in.

Interesting article. A few questions:

1 - what is a good source for permeability of different thicknesses of plywood / OSB? I'm seeing values all over the place on-line.

2 - could 1/2" OSB also work?

3 - what if I did not tape the OSB & instead used a different method for air sealing (i.e. external housewrap) Would the OSB still count as 40 ng or would the gaps make it higher?

Andrew

Hi Andrew

I've also seen some fluctuating numbers on OSB, I'll see about tracking down some solid stats for you on that.

Keep in mind that the 40 NG rating is for vapour permeance, not air permeance. How you choose to seal the joints may affect how airtight it is, but it will have no tangible effect on the vapour permcance. In truth it could actually affect it, but in the most miniscule way, in that where you put tape or any other sealer may be slightly more impermeable at that spot. The impact of that is along the lines of the 'butterfly flapping its wings' impact. Scientifically measurable but that's about it. Check out our page on air barriers and vapour barriers for a better idea of why that is of no importance. http://www.ecohome.net/guide/difference-between-air-barriers-vapour-barriers

Thanks Mike,

This article is describing something not far from the double-wall construction people are using sometimes here in Yellowknife. We are talking about up to 10" of exterior insulation.

I'm thinking that if untaped OSB gets 40 ng, then we can leave out the poly and/or taped joints altogether & use the (very carefully sealed) outer tyvek layer as the air-barrier.

You must meant the REMOTE wall? Great design for that climate. The first house of our Net Zero Heat program did that, among other things he had I believe 13 inches of exterior foam, and ended up with an R80 wall. That's in the Saguenay, Quebec.

Given that you are a far north climate, that can alter what is the 'ideal' building envelope compared to the vast majority of Canadian homes, so before you commit to anything I'd check the numbers to be sure.

40ng is great in southern Canada because your wall can dry to the inside a bit during hot humid summers, but maybe you don't have the same issue where you are. Poly is great for winters, its just in the summer when it is a problem, as the extreme heat and humidity reverses the vapour drive, so for a few months the vapour barrier is on the wrong side. Without those extreme conditions you may actually be best with a poly. Its all pretty climate specific, so before you design a northern Canadian wall around our recommendations for southern Canadian wall, I'd check what your building code recommends there.

The REMOTE wall is used in Alaska, but very rarely here. That much foam is just too expensive.

Most folks these days use a 2x6 wall with poly just under the drywall and a couple of inches of foam on the outside. That gets them just over the EGH-80 minimum that is local code. But air leakage is a big problem.

I was talking about double 2x4 walls ~12" thick wall with batt insulation all the way. Poly on the outside of the sheathing on the inner wall to protect it from the electrical punctuations. Much cheaper than the REMOTE method and uses greener materials too.

A

If you want to go to all of this extra trouble and expense might I recommend that you just build all of you exterior walls with ICF. Better Performance and no chance of rot ever.

Apparently North American manufacturers do not test the air tightness of OSB and different products can behave differently - some stories of OSB leaking can be found here:

http://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/musings/osb-airtight

Any Canadian experiences similar to this?

There is effort and investment however you build, this is one option. It is certainly more affordable than ICF, concrete isn't cheap. I'd consider ICF below grade, but above grade the cost to R value ratio is not too favourable for ICF. This technique can make for a super airtight building envelope since you don't puncture your air barrier with electrical work, and the insulation is somewhere around double that of ICF for likely not much different cost. And from an ecological standpoint, wood is a renewable resource, while concrete releases a ton of green house gases per ton produced, so unless you are building a parking garage on top ICF can be a hefty cost to homeowners and the planet for its level of performance. Thanks for weighing in, regards.

Do you have concerns with off gasing?

"4 inch wax-impregnated wood fiberboard on the exterior"... can someone explain this?

I have read this article a few times and understand where you are coming from with this idea of an OSB interior V.B. ..... in southern Quebec or Ontario this would make more sense.... you have more humidity. But here in the dry prairies where we get less than 20 inches of rain a year we are dry and also cold. For us a class one vapor barrier makes better sense. As Joe Lstiburek will concur with.... but there are also other walls that are built differently that will work very efficient. Like the double stud wall, with dense pack cellulose 12". D.P. cellulose will also absorb and release moisture as needed. You can also incorporate a 2x4 service wall and this will elliminate any punctures to the v.b. Then a liquid air barrier on an exterior 7/16 OSB with 2" of EPS rigid board will keep the sheathing warm. Especially if you have radiant heating in the floor. There are many different wall systems. Each to there own climate area, budget and preferences.

.. But for us here in the Canadian Prairies the double wall I spoke about covers all the bases and at a more affordable price. And if built tightly will get to the o.6 Air changes per hour the Passive house Institute are looking for. D.P. Cellulose is a great product and very friendly for the environment.

Hi Bob,

Thanks for your input, and you’re right – the regional climate should always be considered when designing a building envelope. 6-mil poly vapor barriers are standard fare in home construction up north, and often times they can pose a big problem. Putting the OSB ‘vapor retarder’ in the center of a wall assembly instead of the exterior can improve the ability of walls to dry, in winter as well as summer when homes are cooled. Proper home design will change by climate just as the clothing you wear will change, and there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution for home construction in Canada and the US.

hi. what about using OSB on the interior as described in the article but on a concrete block house. the house is currently under reno down to nothing but a concrete wall. Do i need to add a furring strip against the concrete and then the osb? the exterior of the house has a complete wrap of 18cm of rock wool insulation lamba 0.030 value. thanks.

No, I think that would be a disaster. any foundation wall made of concrete or cinderblocks would be a constant source of humidity, so your OSB will turn to oatmeal in no time. Footings are almost always sitting right in the ground, so they continually absorb moisture which migrates up the wall. And moisture goes right through Rockwool insulation so that would be no help at all. There are a few pages in our discussion forum on block foundations, try this one first -

How do you apply vapor barrier and insulation to a CMU house?

CMU means 'Concrete Mass Unit' which is a fancy way to say 'cinderblock'. even in that question there are links to other block wall foundation repair discussions, so see if you find your answers there and if not, pop on a question of your own.

Old post I know, but can someone comment on the vapour permeability of the wax-impregnated wood fiberboard? It sounds like that could be fairly vapour resistant itself (just a guess), but I'd imagine given the source of this information, it must also be vapour permeable?